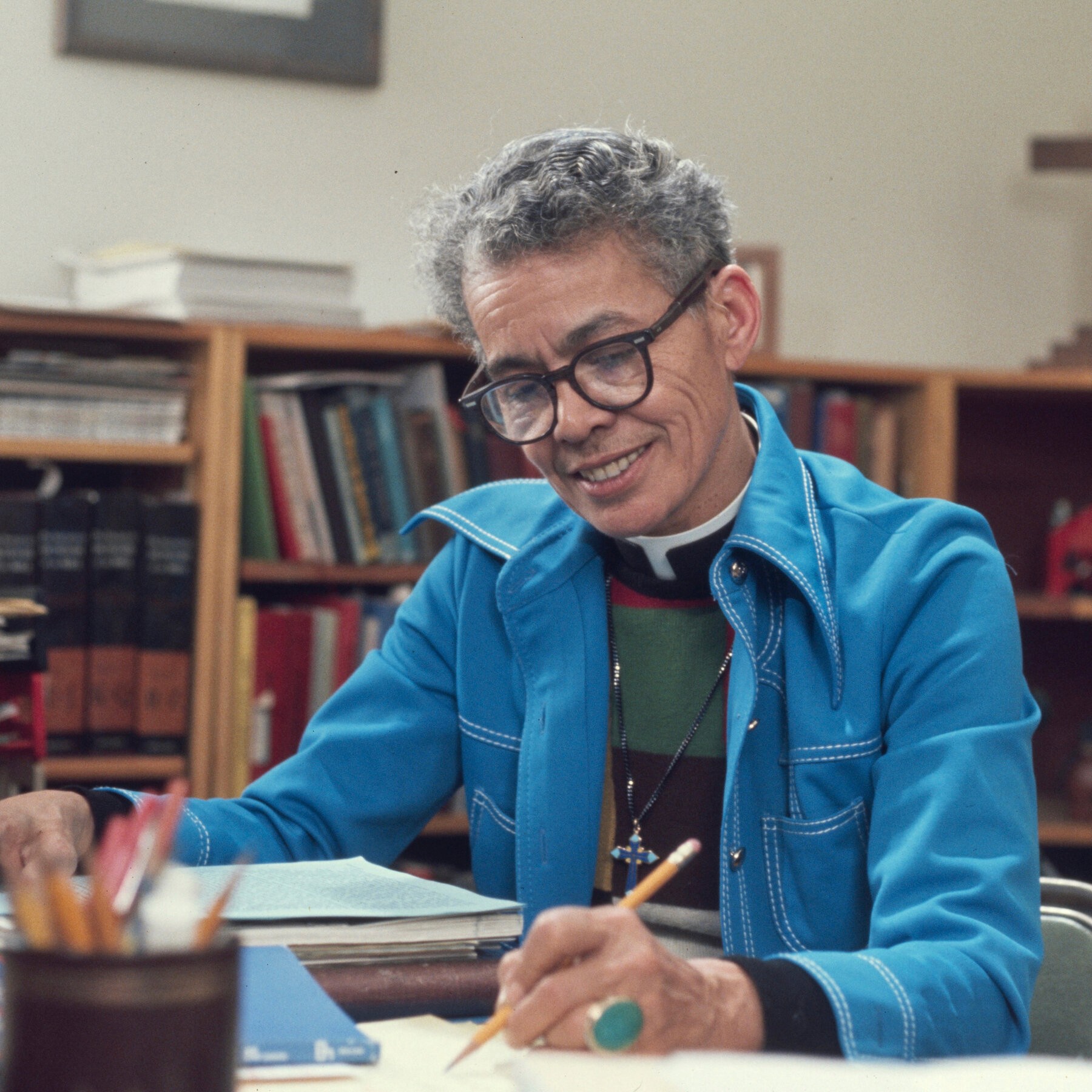

Pauli Murray Founds National Organization for Women

Jun 30, 1966

Born in North Carolina, orphaned, and adopted by her aunt Pauline Fitzgerald, Pauli (born Pauline) was educated by her aunt at a segregated school. Even at a young age, she began individually protesting unjust laws. She refused to get on segregated streetcars, opting to walk or ride her bike instead. She did not go to the movies because she did not want to sit on the balcony. Instead, she became an avid reader. After graduating high school, she worked for a year to earn enough money to attend Hunter College in 1929, where she became one of four Black students in a class of 247. While in college, Murray began calling herself Pauli. Convinced she was a man in a woman’s body, she tried unsuccessfully for years to obtain hormone therapy. She would wear pants and cut her hair short but was never able to live as her gender – something that would continue to plague her for the remainder of her life. She applied to the University of North Carolina to study sociology but was rejected based on race. Years later, she applied to Harvard Law School for graduate study but was denied because of her gender. Murray found herself – an educated Black woman for the time – pushed out of academia because she sat at the intersection of two sources of oppression: her race and gender. This intersectional oppression (a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw) would profoundly impact Murray’s life, fueling and informing ideas that would later become pivotal cases in U.S. history. Murray’s work heavily influenced both Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Thurgood Marshall, and many of the ideas that made waves in the legal system at the time originated with Murray. In March 1940, Murray and a friend traveled through Virginia by bus to North Carolina. They refused to move to a broken seat on the bus, which resulted in their subsequent arrests. The NAACP attempted to use this case to challenge segregation laws, but a judge changed the charge to disorderly conduct to sidestep the challenge. This was one of the events of Murray’s life that inspired her to attain a law degree from Howard University. During her time there, Murray and fellow students planned sit-ins and picket lines and integrated two restaurants years before what we traditionally consider the Civil Rights Era of the 1960s. Pauli Murray’s early contributions set a foundation for political strategy and passion that would later define the movement. During one of Murray’s courses at Howard, she argued that the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause should be used to bring down Plessy v. Ferguson. Despite vehement disagreement from her male classmates and determined she was correct, she bet her Professor Spottswood Robinson $10 that Plessy would be overturned within 25 years. Ironically, Robinson kept the paper and referred to it ten years later when he, Thurgood Marshall, and the NAACP were preparing Brown v. Board of Education. As we know, they won that case. What is not widely known is that Pauli’s analysis was the foundation for their successful arguments. In 1971, when Ruth Bader Ginsburg presented Reed vs. Reed – her first gender equality brief to the U.S. Supreme Court – she credited Pauli Murray for delineating the connection between race and gender and her approach to using the equal protection clause to litigate gender equality. These were crucial steps that laid a foundation for her case. It is essential to Black futures everywhere that we understand and acknowledge Murray’s contributions to our rights as women and our freedoms as Black people. In our classrooms, we learn about Brown vs. Board of Education. We know about Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her women’s rights project. Why have we not heard about Pauli’s contributions to both movements?